The greengrocer’s gambit

Canada PM Mark Carney broke the first rule of the rules-based order: don’t talk about the noble fiction.

In 1970, the Nazi-fighter turned economist Albert Hirschman published a slim, punchy book called Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. The idea was so deceptively simple it seemed obvious in retrospect: When you’re dissatisfied with an organization — a company, a political party, a country — you have three options. You can exit by leaving. You can use your voice to complain and organize. Or you can remain loyal and cross your fingers, because the costs of the other two options are too high.

The complexity comes from how these options interact. Easy exit undermines voice — why organize if you can just leave? Strong loyalty can enable voice — you fight harder for something you’re committed to. And the threat of exit amplifies voice. “Give me a raise or I’m gone” makes both more powerful than either alone.

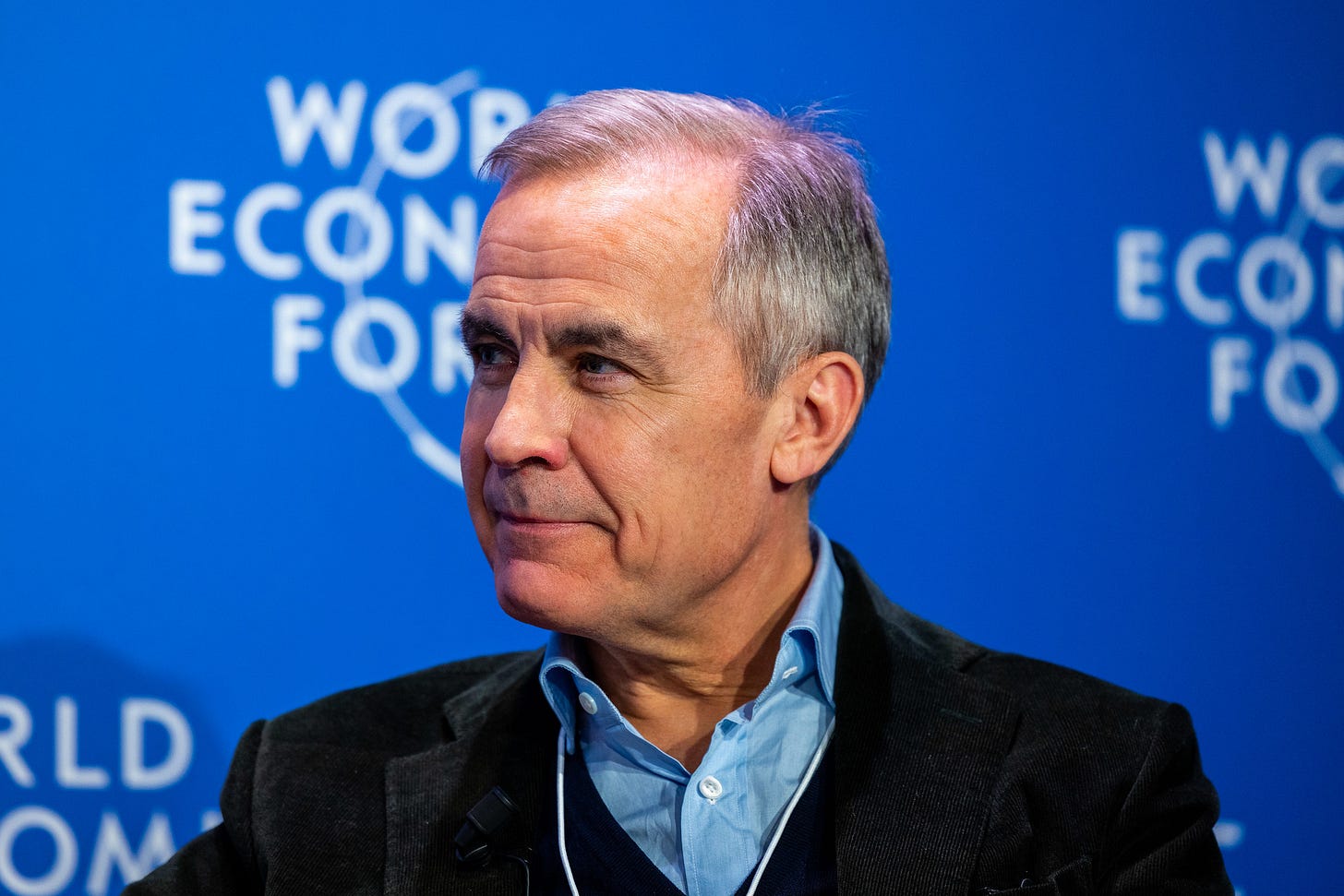

Yesterday at Davos, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney raised his voice louder than any other middle power in my lifetime.

Canada cannot fully exit the American-led system — geography and economics make that impossible. But loyalty has become untenable now that Trump’s America refuses to even pretend to play by the rules and continually threatens Canada’s sovereignty.

So Carney has built the infrastructure for partial exit: renegotiating trade with China, India, Qatar, ASEAN and the EU; doubling defense spending and securing European procurement arrangements; signing strategic partnerships across four continents. And then he used his voice.

Carney used Václav Havel‘s 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless” to frame his remarks. Havel, a dissident Czech poet who later served as his country’s president, described a greengrocer in communist Czechoslovakia who places a sign in his window each morning: “Workers of the world, unite!” He doesn’t buy the slogan — truly, no one does. But he displays it to avoid trouble. And because every shopkeeper does the same, the whole system persists, not by force, but because of the fear-making power of collective performance.

Carney acknowledged what you’re not supposed to: the rules-based order was American hegemony, and for most middle countries most of the time that was a good thing.

For decades, Carney says, countries like Canada “placed the sign in the window.” They praised the rules-based international order, benefited from its predictability, and avoided calling out “the gaps between rhetoric and reality” — that the strongest exempted themselves when convenient, that international law applied with “varied rigor, depending on the identity of the accused or the victim.”

Carney acknowledged what you’re not supposed to: the rules-based order was American hegemony, and for most middle countries most of the time that was a good thing. “This fiction was useful” he said.

But now, Carney argued, “this bargain no longer works.” And then he said the thing no Western leader ever, ever says: “You cannot live within the lie of mutual benefit through integration when integration becomes the source of your subordination. Friends, it is time for companies and countries to take their signs down.”

In other words, he names the noble fiction — and says it is no longer noble.

There’s a reason no one talks about the noble fiction: to name it is to shatter it. When I was at the State Department, someone somewhere decided we needed to write a big keynote speech or a splashy essay in Foreign Affairs defining and defending the rules-based international order. The job landed on my desk.

I was relatively new to foreign policy and had always been confused about what the “international rules-based order” was exactly and why it had to be such a mouthful. So I set about trying to figure it out. I asked policy advisors in the U.S. mission to the United Nations, who pointed me to State’s Policy Planning office. They told me to talk to the National Security Council. The NSC sent me to some lawyers. The lawyers told me there was no official definition besides “an international order based on rules.” I felt like I was taking crazy pills.

Nations dress up their self-interest as universal principle, and then they come to believe their own propaganda.

The speech/essay never happened. I suspected, at the time, that perhaps the phrase was designed to resist definition, so as not to expose the occasional gaps between what we said and what we did. Reinhold Niebuhr diagnosed this problem when he argued that nations dress up their self-interest as universal principle, and then they come to believe their own propaganda.

I’m not sure if we had just come to believe our own propaganda — I do believe the rules-based order was the closest the world’s powers have ever come to binding their own might, and that the UN was an incredible force for peace — but Trump shattered any pretensions or illusions about the nobility of American hegemony. So all that was left was the fiction. Carney was just the first leader honest enough to dispel the fiction, too.

I’m a U.S.-Canadian dual citizen, and I travel to Canada several times a year. But when we went last spring to Toronto to run a Riskgaming scenario on AI and national security, right after Trump had started making hoopla about turning Canada into the 51st state, I was shocked.

Unlike the United States, one never saw Canadian flags in Canada. It just wasn’t a thing. Suddenly I saw the maple leaf flying everywhere — apartment windows, office parks, construction sites. When I went to grab a coffee, the café had renamed the Americano the “Canadiano.” American liquor was pulled from shelves, apps like Maple Scan helped shoppers avoid U.S. products, and border crossings plummeted.

The political shift was just as dramatic. In January last year, the Liberals were polling at 20 percent. By April, they’d won. Carney was propelled into office by pure Canadian defiance in the face of American imperialism. So when he speaks his truth, he’s also speaking to his base.

A former leader of Canada’s Liberal Party, Michael Ignatieff, quoted Freud in an excellent recent essay on the narcissism of small differences — Canadians defining themselves against America precisely because the countries are so similar. But truth be told, what I saw wasn’t narcissism. I saw fear sharpening into resolve. Carney is channeling that energy at the precise moment it gives him leverage.

What Carney proposed with his leverage is “variable geometry” — essentially, different coalitions for different issues, middle powers coordinating for collective bargaining power. So for Ukraine, that’s a coalition of the willing. For Arctic sovereignty, solidarity with Greenland and Denmark. And on AI, that means cooperation among democracies to avoid choosing “between hegemons and hyperscalers” — a striking phrase that names tech companies as somewhat-sovereign actors.

Unfortunately, variable geometry doesn’t provide a forum for resolution when coalitions harden or disputes arise. And while Carney named the UN, WTO, and COP as institutions “under threat,” he offered no vision or prescription for preserving them. The threat of World War III looms large.

And the AI math is brutal. According to the Federal Reserve, the United States controls 74 percent of global high-end AI compute; China holds 14 percent; the EU has less than 5 percent. Canada doesn’t register. U.S. hyperscalers are spending over $400 billion annually on AI infrastructure — more than five times China’s investment. The logic of concentration is relentless: compute, data, and talent flow toward whoever already has the most.

Canada does have real leverage as the only Western nation with serious reserves of cobalt, graphite, lithium, and nickel, all of which are essential for the chips and batteries that power AI. But critical minerals are inputs, not capabilities. Unless open source wins, it’s unclear how even the strongest collective bargaining group could have real leverage over the AI race’s winners.

But I think Carney knows this. As he conceded, “A world of fortresses will be poorer, more fragile, and less sustainable.” His gambit isn’t that variable geometry is a great idea or solves all these problems, but rather, that it’s the least-bad option available to middle powers like Canada.

Havel spent his life arguing that truth-telling was the most radical act available to the powerless. But once he became president, he discovered that the dissident’s clarity doesn’t easily translate into statecraft. A literal poet, he never quite figured out how to go from campaigning in poetry to governing in prose.

Carney is attempting to succeed where Havel failed, to be both the greengrocer and the prime minister all at once. “We are taking the sign out of the window,” he declared. “We know the old order is not coming back. We shouldn’t mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy…”

Nostalgia is not a strategy, but the greengrocer’s gambit is. Carney has broken the first rule of the rules-based order: don’t talk about the noble fiction. He’s chosen to raise his voice right at the moment of maximum pressure, and bet his country’s future on the power of ending a pretense.

The sign is down, the noble fiction is dead. Now we find out if the truth has any leverage, or if Canada’s threat of exit is real.