Somehow, I always forget the shrill staccato of the emergency push notifications I receive when I visit South Korea. They range from the quotidian (“male, 68 years old, last seen in the park”) to the unavoidably political. On my vacation last year, the pushes were about the trash balloon flotilla North Korea’s Comrade Kim kept floating over Seoul to dump waste on unsuspecting urban dwellers. Stay away, I was commanded.

This time, the crisis was more serious than the clownish antics of the man up north. A backup battery had caught fire at the country’s National Information Resources Service data center, near where I used to live in Daejeon. Like other battery fires, the flames rapidly spread, engulfing and destroying the entire building despite the furious efforts of dozens of firefighter companies. More than 600 critical government services were knocked offline. The data center was miles away from me and posed no immediate hazards, but its centrality ensured another salvo of urgent messages were pushed out to the entire country.

A decade’s worth of work by an estimated 750,000 civil servants vanished up in smoke.

The fire was just the start of this rolling catastrophe. A review found that terabytes of critical files stored on the government’s privately-managed G Drive system had been destroyed. As reported by the Joongang Daily, “… due to the system’s large-capacity, low-performance storage structure, no external backups were maintained — meaning all data has been permanently lost.” A decade’s worth of work by an estimated 750,000 civil servants vanished up in smoke.

Some systems that were unaffected — like immigration — were nevertheless swept up in the aftermath. South Korea, in the middle of a rapprochement with China to thaw relations that had cooled with the deployment of America’s THAAD weapon system all the way back in 2016, had agreed just days before the fire to allow visa-free entry to Chinese tour groups. Korea’s right wing, which aggressively opposes the Chinese Communist Party, was quick to suggest Beijing started the fire to permit hordes of Chinese tourists to enter the country and begin a national invasion. This story became a viral meme across X, requiring strenuous denials from government officials and exacerbating the country’s fragile political environment.

Push notifications kept coming as some systems came online and others remained dead. The post office and the country’s finance system were offline, a disaster with the country’s most important holiday, Chuseok, approaching. Even now, two weeks after the fire, only 36.4% of the disabled government services have been restored, and only 30 of the top 40 most critical are functioning.

I have been a dauntless advocate for government digitalization, and I continue to believe artificial intelligence has the ability to radically improve the quality and efficiency of services, perhaps even ushering in a new era of fiscal sanity for America’s cities. After all, a fire could destroy America’s retrograde paper-based records just as easily as it can melt silicon, and data is a lot easier to back up.

Yet, our reliance on centralized systems for such a widespread number of critical services demands deeper introspection. After all, this battery fire isn’t the first time South Korea has faced this type of crisis; back in 2022, a data center fire at Kakao knocked out the country’s most popular app and payment platform, bringing the entire consumer economy to a halt and ultimately leading to the resignation of co-CEO Whon Namkoong. One of the world’s most digital societies has discovered living with the machine has significant downsides.

More push notifications sprang up on my home screen. I was on vacation, and the crisis prompted me to return to E.M. Forster’s magnificent 1909 short story, “The Machine Stops.” He envisioned a deep future in which humans had become enmeshed with the Machine, relegated to individual and identical underground caves that provide all light, nourishment, entertainment, communication and living quarters at the push of a button.

The Machine responds instantly to requests, yet the humans who inhabit this dystopia seem to lack even the most fundamental of freedoms.

In the story, Forster twists his readers’ notion of individual agency. The Machine responds instantly to requests, yet the humans who inhabit this dystopia seem to lack even the most fundamental of freedoms. The human thirst for adventure and exploration is replaced with a stunted somnambulance, a constant search for unrealized thrills from the comfort of the Machine’s embrace. “The room, though it contained nothing, was in touch with all that she cared for in the world.”

Not only does individual agency get redirected, the Machine itself starts to absorb its energy. “But Humanity, in its desire for comfort, had over-reached itself. It had exploited the riches of nature too far. Quietly and complacently, it was sinking into decadence, and progress had come to mean the progress of the Machine.”

Forster was sending his own emergency push notification to critique progress and technocracy, themes that had been explored by contemporaneous authors like H.G. Wells in “A Modern Utopia.” Italian Futurists were then exalting the aesthetics of machines like the automobile as a transcendent form of humanity’s unbridled intellect. Forster responded by showing the dangerous dependency these machines foisted on humans.

For indeed, the miraculous Machine is also dying. The Mending Apparatus that keeps the Machine running requires its own mending, and it is falling behind. Things start to break, first the music, then more serious systems. Chaos erupts. Forster turns poetic: “Century after century had he toiled, and here was his reward. Truly the garment had seemed heavenly at first, shot with colours of culture, sewn with the threads of self-denial. And heavenly it had been so long as it was a garment and no more, man could shed it at will and live by the essence that is his soul, and the essence, equally divine, that is his body.” Humanity’s complete dependency on the Machine ultimately proves not liberating, but lethal.

Forster argues for the importance of connection and direct experience, both of which now terrify a humanity used to the mollycoddling embrace of the Machine. Yet his secondary motivation is to point out that over-reliance on external tools beyond our own faculties has a serious cost all its own.

What’s needed more than ever is a bit of chaos engineering.

The Machine exists today, and it has enveloped us. Reading a bunch of articles on AI on the plane ride over to Asia, I was struck by the number of writers and sources who noted they sometimes went hours without once thinking about what they were doing. AI models are so perfect at predicting the next required action that they can run autonomously of their human masters. Some college students haven’t read or written a single line of prose and still string together straight As. Forster’s garment fits snugly.

What’s needed more than ever is a bit of chaos engineering across society. I brought up the methodology last year, but the idea is to carefully and intentionally break technical systems and see what fails for the end user. Turn off a data center — does software break? The network goes down — what are the repercussions? Are we prepared with redundancies, and can we degrade service in a way that still makes it useful?

Yet the concept is even more useful when we include society itself as part of the system. What happens if our credit card processors fail — can we still operate our businesses? Yesterday at my coffee shop, the online ordering system was receiving requests but not relaying them to the store due to some coding bug. An enraged crowd of customers was stewing, and the store employees had no idea what to do. Call it Riskgaming, or just good contingency planning, but businesses should never fail to take a customer’s money due to something as brittle as a modern PoS system. We’re just serving coffee after all.

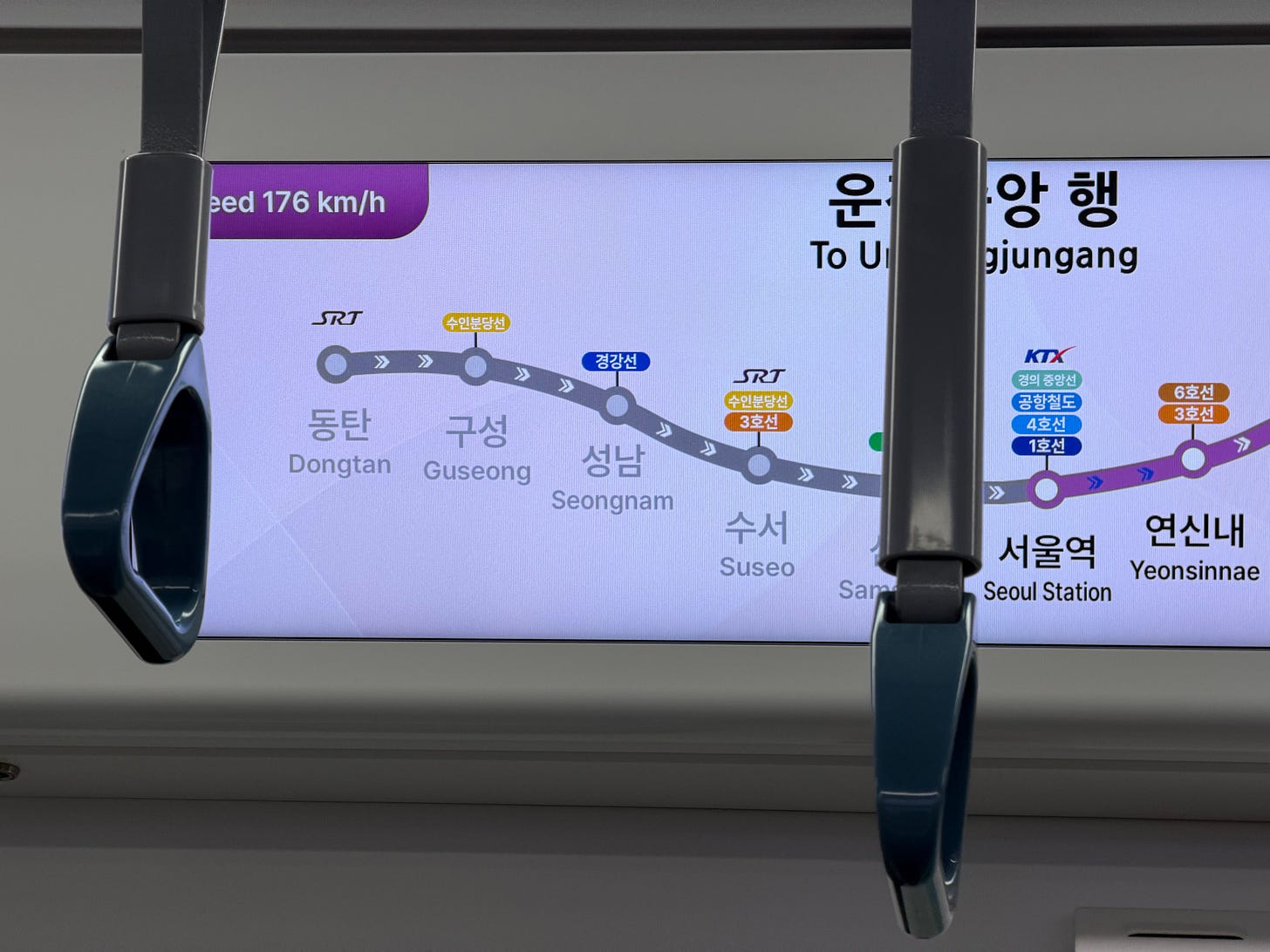

Turn-of-the-century progressives were certainly correct: technology affords us tremendous luxuries. In Seoul, I rode the new segment of the GTX-A high-speed subway line, which whisks travelers at 110 miles per hour between their destinations. That’s Penn Station to JFK Airport in about 10 minutes. We don’t need to give up these wonders just because they can fail, but nor should we give up our ability to use alternatives either. We’re only ever one push notification from disaster.

Looks like half the internet needed a lesson in chaos engineering.

https://x.com/IterIntellectus/status/1980191908090855567

South Korea is great. I lived there for 14 months back in 2000-01 and though I spent my working days closer to the DMZ I spent every weekend in Seoul. The city then seemed like it was passing through a liminal period of entering the super developed world while also possessing sidewalk fish markets and lots of counterfeit clothing. I never had anything but positive interactions with the people. What an awesome place to be young.