Decline and fall of the U.S. science empire, the promise and perils of “study mode,” and how we got hooked on corn syrup. Plus Trump’s Potemkin economics.

Reminder: Riskgaming Runthrough August 7 in NYC

We’re hosting a beta test of our latest Riskgaming scenario, Gray Matter, on August 7. It’s designed by our very own Laurence Pevsner, and it explores the future of neurotech in a world of faulty information. It’s a fun, one-hour cocktail game, perfect for a Thursday night in New York City.

From Lux Capital

This week, Lux portfolio company Ramp, which uses AI to automate companies’ financial software stacks, raised $500 million in its latest found of funding, valuing the company at $22.5 billion. The round was led by Iconiq. In case you think we accidentally republished this news, we did not. Ramp raised $200 million at a $16 billion valuation a few weeks ago.

Another one of our companies, Runway, is teaming up with IMAX. Last spring, Runway held a one-day film festival to showcase AI-enhanced movies. Runway and IMAX will now offer commercial screenings of ten of the finalists from the festival.

From around the web

1. Make science Soviet again

I’ve spent a lot of time this week thinking, writing and talking about the future of science in America after U.S. President Donald Trump’s funding cuts. As broken as our system was before Trump, it is undeniable that we may be entering a much darker period. How dark? I find some reason for optimism, others less so. On that score, Lux scientist-in-residence Sam Arbesman recommends the latest from Ross Andersen in The Atlantic. Ross charts the decline of the Soviet scientific empire and finds eerie similarities to the United States today.

The future of Soviet science was looking grim. Within a few years, government funding would crater further. Sagdeev’s most talented colleagues were starting to slip out of the country. One by one, he watched them start new lives elsewhere. Many of them went to the U.S. At the time, America was the most compelling destination for scientific talent in the world. It would remain so until earlier this year.

2. Kernel of truth

Another result of Soviet decision-making during the Cold War? Americans’ use of corn syrup in … just about everything. In Bloomberg, Stephen Mihm tells the long tale of unintended consequences. From grain embargoes to cheap corn syrup to import restrictions on sugar to total reliance on the corn-based-sweetener to the Trump administration’s MAHA war against it, the back-and-forth in Stephen’s piece reminded me of everything we talk about in Riskgaming.

The Soviets, oddly enough, saved the day. After they invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, President Jimmy Carter slapped a grain embargo on the Soviet Union, ending all corn shipments. Prices tumbled, suddenly making high fructose corn syrup a much cheaper alternative. In response, Coca-Cola Co. made the momentous decision to replace some of its reliance on cane sugar with the new sweetener in 1980.

3. Midterm crisis

With America’s science sector in tumult and fewer sugary drinks to fuel late nights, what are future researchers to do? The easy answer would be to find some quick fixes on ChatGPT. The only-very-slightly harder one would be to use ChatGPT’s new “study mode,” meant to help them come to their own conclusions. Lux podcast producer Chris Gates flags a piece in Wired by Reece Rogers, who explains why study mode won’t solve the fundamental tensions between AI and education.

ChatGPT’s study mode is an attempt to foster more thorough engagement on a topic with users by throwing questions back at them and asking for more context about their learning goals. “Instead of giving a very long, drawn-out answer up front, it's first asking you, ‘Hey, what are you trying to optimize for? What's your current level?’” says Abhi Muchhal, who works on the product team at OpenAI.

4. Less is not more

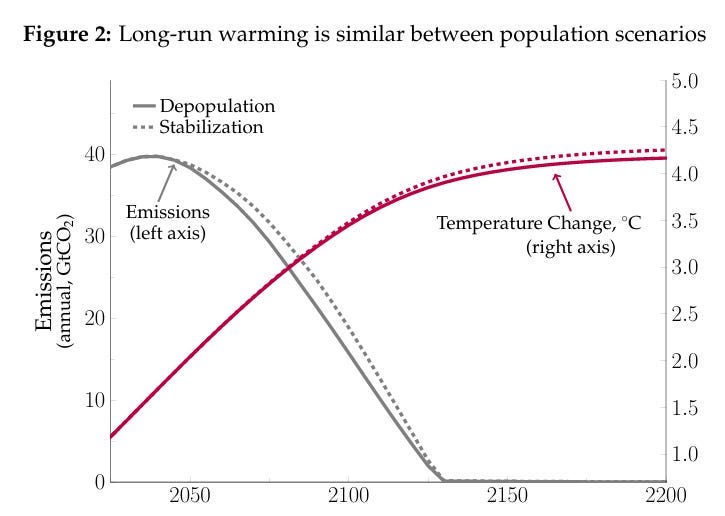

You may ask: What does it even matter if far bigger things are going on, like the world becoming uninhabitable due to climate change and the global population set to shrink? On Sustainability by the Numbers, Hannah Ritchie takes on the common argument that population decline may bring lots of bad things, but it could at least solve our emissions problems. Not so fast, she argues. Population changes will come far too late. H/t editor Katie Salam.

Let’s think about it first in terms of per capita emissions. In the emissions curves above, global average per capita CO2 emissions would still be around 4 to 4.5 tonnes per person in 2050. When they’re still at this “high emissions” point, the difference in the global population is still very small. That’s because it takes a while for changes in fertility rates to filter through to the global population. There are probably around 250 million extra people in the “high” population scenario in 2050. Together, their additional emissions would be around 1 billion tonnes per year.

That sounds like a lot, but it’s less than 2% of annual emissions, and a tiny amount of the total cumulative carbon emissions (which is really what matters for warming) that we’ve accumulated in the atmosphere over centuries.

Trump firing the labor statics director for unpopular data feels like the most Soviet thing of all..

https://stocks.apple.com/Ae3B2qZINTPaj6YPgWGnwsQ