Side note: Join Riskgaming in NYC next week on August 7

We’re hosting a beta test of our latest Riskgaming scenario, Gray Matter. It’s designed by our very own Laurence Pevsner, and it explores the future of neurotech in a world of faulty information. It’s a fun, one-hour cocktail game, perfect for a Thursday night in New York City.

What matters more: actual economic performance or perceived economic performance? This is a profound question with unsettling answers. Good fundamentals are certainly correlated with better perceptions: if an economy is growing rapidly, that growth should pulse through the zeitgeist. Yet, perceptions can both lead and lag actual performance, and the mismatch can have a wild influence over the future trajectory of the economy.

Here’s a much more obvious question: Is actual performance or perception easier and cheaper to change? Improving fundamentals potentially requires prodigious outlays of funds, long time horizons, and a will to dismiss implacable incumbent interests. Meanwhile, perceptions can be meme’d, sometimes even for free.

Thus, we find ourselves in a unique moment in which both of the world’s only two superpowers are avoiding calculating the true performance of their economies and are instead airbrushing perceptions.

The China case is more brazen and has been going on for longer. As The Wall Street Journal summed up a few months ago, as a result of a broad data crackdown, hundreds of the country’s statistics are no longer published. “In most cases, Chinese authorities haven’t given any reason for ending or withholding data. But the missing numbers have come as the world’s second biggest economy has stumbled under the weight of excessive debt, a crumbling real-estate market and other troubles—spurring heavy-handed efforts by authorities to control the narrative.”

Fixing China’s fundamentals is a gargantuan task — think building a $170 billion dam on Tibet’s Yarlung Zangbo River big. Fixing perceptions of those fundamentals though is much easier. Delete the right data sources and funnel narratives through a controlled and compliant press, and the economy is whatever the Beijing authorities want it to be. What they want right now is for everyone to think the economy is growing well and remains a competitive destination for investment. Pesky aggregates like “inflation” and “GDP growth” are incendiary sparks that could burn down the Potemkin cities that litter China’s countryside.

America’s white-hot economy, with stocks at all-time highs, wouldn’t seem to need the same statistical massaging. Yet we find ourselves traveling down the early steps of a similar path.

Is this just benign neglect that comes from a chainsaw approach to core government functions, or is it instead a nefarious plot to manage the economic narrative through a turbulent time?

Thanks to cuts in federal government employment, America’s own economic data is becoming increasingly unreliable. As reported yesterday in The New York Times, “The Bureau of Labor Statistics last month said it was reducing its collection of data on consumer prices, and had stopped gathering data entirely in several areas. On Tuesday, the agency provided more details on the cutbacks and indicated they were more significant than previously understood.”

The news offers a good Rorschach test on the Trump administration. Is this just benign neglect that comes from a chainsaw approach to core government functions, or is it instead a nefarious plot to manage the economic narrative through a turbulent time?

The balance of the evidence is not sanguine. Americans are deeply concerned about consumer price inflation, which also happens to be the president’s worst issue in polls. Nor does it help that the president is actively trying to goad Fed chair Jay Powell to lower interest rates to boost economic growth. The Fed ignored the president’s overtures this week, although two of Trump’s appointees on the board of governors dissented, the first time in decades the Federal Open Market Committee’s decision had more than one member opposed.

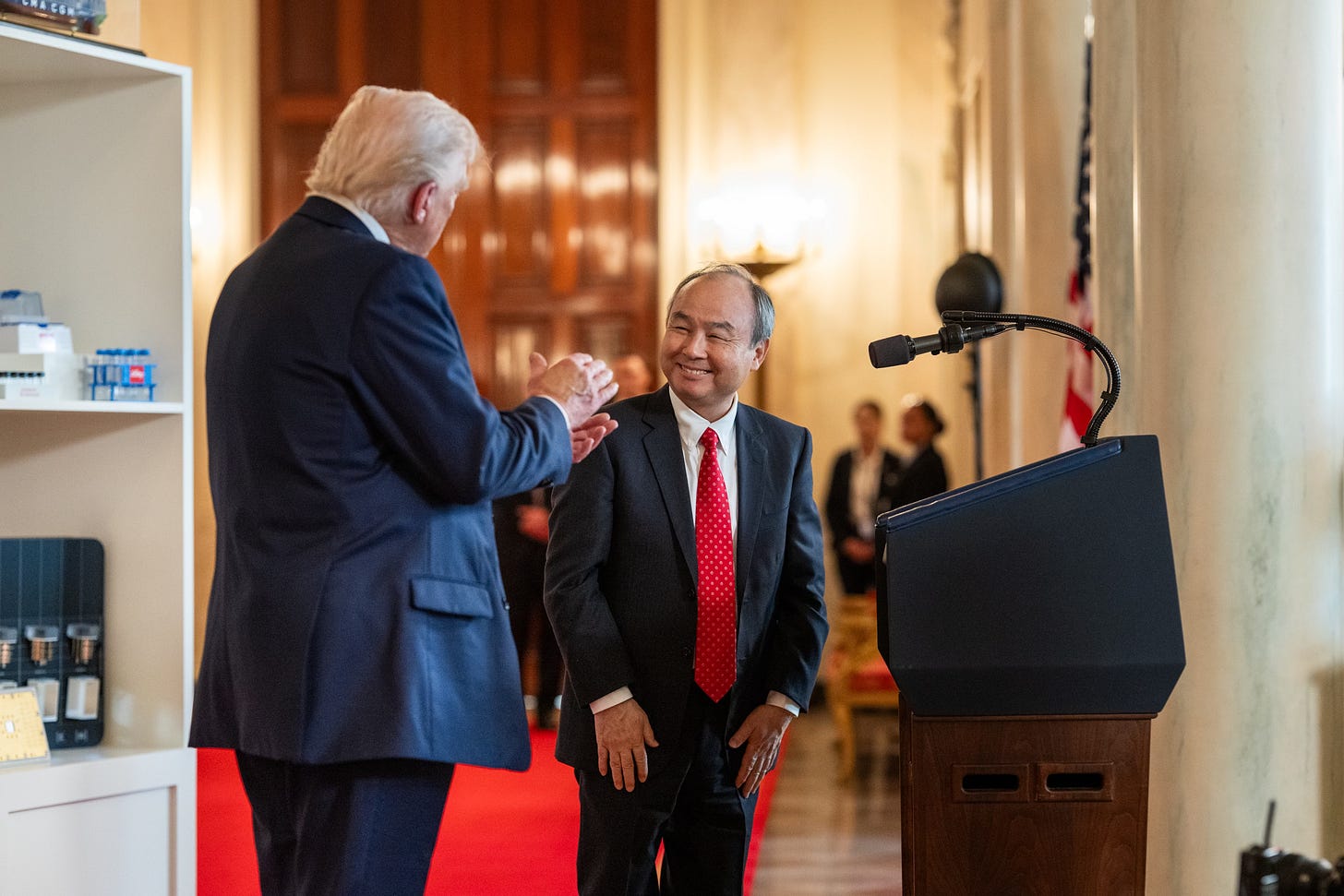

Or take Project Stargate. Trump, OpenAI’s Sam Altman and SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son announced a $500 billion AI infrastructure project that would be the greatest compute buildout in U.S. history. There’s just one problem: it’s not happening. As the WSJ reported last week, “While the companies pledged at the January announcement to invest $100 billion ‘immediately,’ the project is now setting the more modest goal of building a small data center by the end of this year, likely in Ohio, the people said.”

This is economic narrative management, par excellence. Offer an incredible development story covered widely in the press with massive headline numbers, and then conduct a massive pullback as none of those numbers are realized. Yet the aura of boundless growth lingers. All it costs is a press conference at the White House.

The presidents of both China and America have reached a similar conclusion: omitting or massaging data is the path of least resistance for growing their respective economies. Both are taking a page from Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who fired the head of the Turkish statistical institute in 2022 when the country’s inflation hit record highs.

We thus seem to be entering a new postmodern period of economic statistics, where influencing vibes outweighs generating quality empirical evidence.

Both leaders need performance now, not later. For Trump, strong economic news is pivotal to undergird support for his tariff negotiations in the face of American fears about inflation. For Chinese president Xi Jinping, who is staring down a monstrous multi-trillion-dollar debt crisis, narrative management offers the only chance — and a slim one at that — for the country to avoid a roiling period of economic chaos.

We thus seem to be entering a new postmodern period of economic statistics, where influencing vibes outweighs generating quality empirical evidence. It’s one thing for voters to vote their feelings at the ballot box, as they did with Joe Biden and then Kamala Harris last year. It’s another for asset allocators to lack market fundamentals for their investment judgments. Both Xi and Trump understand that by omitting rigorous counter-evidence, they can build the image of the economy as they please and allocators have little choice but to follow along.

Few private entities have the wherewithal to offer competing statistical profiles of nations as large and variegated as the United States and China. It’s no coincidence that the words “state” and “statistics” derive from the same root. The rise of modern states coincides with the increasing ability of governments to manage their people and territories, from censuses and tax assessments to land mapping and zoning. Nascent threads of modern measurement emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries, but only in the last 100 years have we seen the arrival of comprehensive and reliable aggregate statistics, particularly around macroeconomics. It’s an incredible invention — and one that we are losing.

Unfortunately, shenanigans with data work — at least in the short run — but they come at a high cost.

Unfortunately, shenanigans with data work — at least in the short run — but they come at a high cost. Objective truth is expensive to attain, but it is immensely valuable for aligning all actors in a capitalist free-market society around reality. We each may have our own purchase on certain local facts as Friedrich Hayek noted in his essay on “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” Yet, we also need to know what’s happening everywhere else too, given the deep interconnections of the global economy.

I wish this postmodern moment was an aberration, and that a few political leaders wouldn’t fundamentally undermine the basic functioning of the economic system. However, the costs of acquiring objective truth are increasing too. As the NYT pointed out, “Economists have become increasingly concerned about the federal statistical system in recent years. Response rates to government surveys have fallen steadily, gradually eroding the reliability of statistics based on that data. The agencies have been working to develop new techniques that rely less on surveys, but have been hampered by shrinking budgets.”

That challenge mirrors a similar crisis brewing around economic data in the United Kingdom, where the Office of National Statistics has acknowledged that its core publications, including inflation, are increasingly inaccurate. In April, the office cut back on a wide range of publications to try to shore up some of its most important work, with the hope that the prioritization will help the office recover accuracy and stability. Thankfully, that’s a more responsible outcome than in Italy, the statistical agency of which threatened to just stop publishing all national statistics during a budget spat in the early 2010s.

The ultimate costs for data dereliction are, unsurprisingly, incalculable.

Unfortunately, there aren’t a lot of positive developments here, as most leaders seem to be sharing the same lessons with each other. One exception is South Korea, where the new president, Lee Jae Myung, is looking to reform the country’s statistics bureau and potentially make it independent of the powerful Ministry of Finance and Strategy. As an article in the local press noted in June, “the independence of Statistics Korea is considered important because it may be 'resistant to political winds when producing statistics.' This is due to past accusations that Statistics Korea aligned its statistics with the government's preferences.”

Statistics, like indicators for any organization, are the means by which leaders evaluate the outcomes of their decisions. With a shrinking set of increasingly unreliable metrics, countries are impoverishing their own ability to make the right calls at critical moments of uncertainty. Quality statistical collection and analysis will never get the same airtime as a sex scandal, but they are the kernel for high-quality and effective governance. The ultimate costs for dereliction here are, unsurprisingly, incalculable.

I'll take 3 of the $160B dams, please.

I think we've already got a fake missile defense shield.

Thanks for highlighting a trend which is certainly non-obvious for many. It’s deeply concerning and I’d be curious about alternative, more independent sources of data