It’s not every day we get to fête the launch of a new book by one of our colleagues at Lux Capital, so today is a very special day. Lux’s scientist-in-residence, Sam Arbesman, just published his new book, The Magic of Code: How Digital Language Created and Connects Our World―and Shapes Our Future. It’s a deep dive into the wonderful conjuring that comes from coding computers, and Sam explores programming languages, spreadsheets and how code bends reality all in a taut narrative. At its center, Sam is looking to bring the human back into the machine, and create a better computing environment for the future.

Sam, Laurence and I talk about the new book and its major themes, the writing, editing and publishing process, as well as how Sam is feeling about the science and venture world after nearly a decade with Lux.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. For the full discussion, subscribe to the podcast.

Danny Crichton:

Sam, welcome to the show. Unlike many of our guests, you work here at Lux. In fact, you have been here for almost a decade now. Tell us about your role here. You're our scientist-in-residence.

Samuel Arbesman:

My title is evocative but kind of inscrutable, which is a good thing. The way I describe it is that I survey the landscape of science and technology and try to find areas, individuals and communities that could be relevant for Lux in some way.

And then through a combination of writing and speaking and engaging with the public, I'd like to think I'm laying the groundwork for those areas when they are ripe for investment. Or sometimes there is a community that may never be a good investment prospect, but they're just some of the most interesting people that we should have in our orbit.

I think my role is basically just being a weird optionality machine.

Of course, everyone at Lux is doing that to a certain degree. I think my role is a little bit more undirected. Josh likes to talk about the idea of randomness and optionality. And I think my role is basically just being a weird optionality machine.

Danny Crichton:

Serendipity and stochastic searching. In addition to Lux, you've also been a longtime author. Your third book, The Magic of Code, is out now. The first question I always ask is where do these ideas come from. How do you pick one of the many subjects you're tracking and say, “I'm going to spend several years doing the research, the writing, the publishing, the podcast tour to get it all to to the other side.”

Samuel Arbesman:

I mean, the flippant answer is I probably don't think it through that hard. There's a certain amount of, my God, what have I gotten myself into? That being said, I think I often just find myself revisiting an idea over and over in lots of different ways. At that point I say, okay, maybe there is a book here.

This new book is really about the wonders and weirdness of computing. It's something I've been thinking about for many, many years — basically most of my life.

A number of years ago, when our daughter was little, I was reading the stories of Virginia Lee Burton. She's a children's author who wrote The Little House and Mike Mulligan and the Steam Shovel, these great classic books. I noticed they had a particular viewpoint around technology and technological change, and I think I was probably ranting to my wife about this over and over, and she said, basically, “just write about this, stop telling me.”

Danny Crichton:

But I'm curious: You've used this term in the subtitle — digital language — rather than programming language or programming code. Why?

Samuel Arbesman:

I feel like we went through a lot of subtitles. I don't remember exactly which ones we examined. That being said, one of the things I discuss in the book is the interesting similarities and differences between human natural language, programming language and machine language. And I really try to take that seriously and look at the ways in which they're distinctive and the ways in which programmers are trying to articulate certain things alongside operating in the world.

I also discuss it in the context of magic itself. We've had this idea for millennia that we might one day use language to coerce the world around us — through text or spoken word. That's sorcery. And the truth is, about 75 odd years ago, sorcery became a reality. We suddenly could use language to do things in the real world.

Laurence Pevsner:

One of the first conversations we had was about Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea, in which magic is based on knowing the true name of things. You know the name of something and therefore you can control it. That strikes me as similar to what you are talking about with the language of code.

And now you even have this moment where, with vibe coding, you can use AI to code for you so that you don't even have to know the language or fully understand it. You can still cast the magic spell by just talking in English.

Samuel Arbesman:

Yeah, when you're talking about AI and vibe coding, the similarities between sorcery and coding seem particularly salient. I came of age in a certain moment where programming was still powerful, but it also required a great deal of craft and work. Now with vibe coding, maybe we don't have to actually work that hard.

The other side is that there is a whole history of magic actually being somewhat democratized. Like magic was not necessarily just for, I don't know, the archmages or wizards or whatever. There was magic for everyone. In the medieval times, I think there were spells you could use for everyday things like finding lost cattle or whatever it was.

I think there are similar trends within the coding and software world — like making it so it's not just the domain of the specialized software developer but where everyone can build software for whatever they want or need.

Danny Crichton:

What's interesting to me is that the magic has moved. Magic didn't go away in this process. There's actually less knowledge. It's arcane to all of us now, and it lives in this black box that is the computer. How much do you think that changes the nature of how we perceive code and its capabilities?

Samuel Arbesman:

I'm not entirely sure. I do think with a lot of these vibe coding things — or AI enhanced coding, or however we're going to describe it — there is still a tendency to go under the hood and look at the code. And so I don't think it's ever going to be one thing or another — either just manual or just AI. I also think if you use these tools in conjunction with an understanding of a certain amount of programming, you'll be even more powerful.

At the same time, though, coding has always changed. When I learned how to program, I wasn't programming in assembly or binary — that is, doing very basic things close to the hardware. And that was fine. I was using, I don't know, like C++ in high school. And now we're just moving up another level of the stack.

So on the one hand, I might say, no, this is not the way I learned how to do it. And it feels a little bit foreign. On the other hand, it's all part of this tradition of just figuring out ways to coerce the machine into doing our bidding.

Danny Crichton:

Let's go back to the book. So you have this history of digital language, programming and code. You also have a lot on current practices. How do you connect the theory of what code is to the everyday practice of engineers?

Samuel Arbesman:

When I think about the way in which people talk about software engineering or programming, there's the overall utilitarian conversation, which feels a little bit broken. We're either adversarial toward some of these technologies or worried about them or just entirely ignorant.

When you think about code, you should think of it as this almost like humanistic liberal art that connects to language, philosophy, art, biology, how we think

When I think back to my own experiences with computing from when I was younger, there was this sense of wonder and delight with computing. And so the book is trying to widen the aperture and say, when you think about code, you should think of it as this almost like humanistic liberal art that connects to language, philosophy, art, biology, how we think — all these different kinds of things.

The truth is you kind of need them both — both the utilitarian stance and the broader one. And throughout computing history, we've had both. Sometimes we optimize for one versus the other, like early on with mainframes, obviously these were big behemoth machines that were in large organizations, universities, corporations. But alongside that, people were doing weird hacking things like early mini computers. They were developing one of the first computer games, Space War.

It's not like one came first and we lost that sense of fun and now we're just stuck in the corporate world. We've always had both and they build on each other. The more utilitarian kind of software development and programming has made it easier for people to make all the weird funky stuff. And that weird, fun, delightful aspect of coding has also in turn gotten people excited about programming itself, which has allowed people to build some of the other larger pieces of software that are less exciting, but are still very, very important.

Laurence Pevsner:

Your book comes out at a very timely moment. I have felt this shift in Silicon Valley toward hardcore productivity. I was talking to a CTO recently, and he was telling me that all of his new young engineers who are using AI tools code much faster. And because they get results faster, they build on those results and they are racing ahead of senior engineers who want to actually do the coding.

I'm wondering if there are examples of the synthesis? Who are the people who are both playful, but also productive?

Samuel Arbesman:

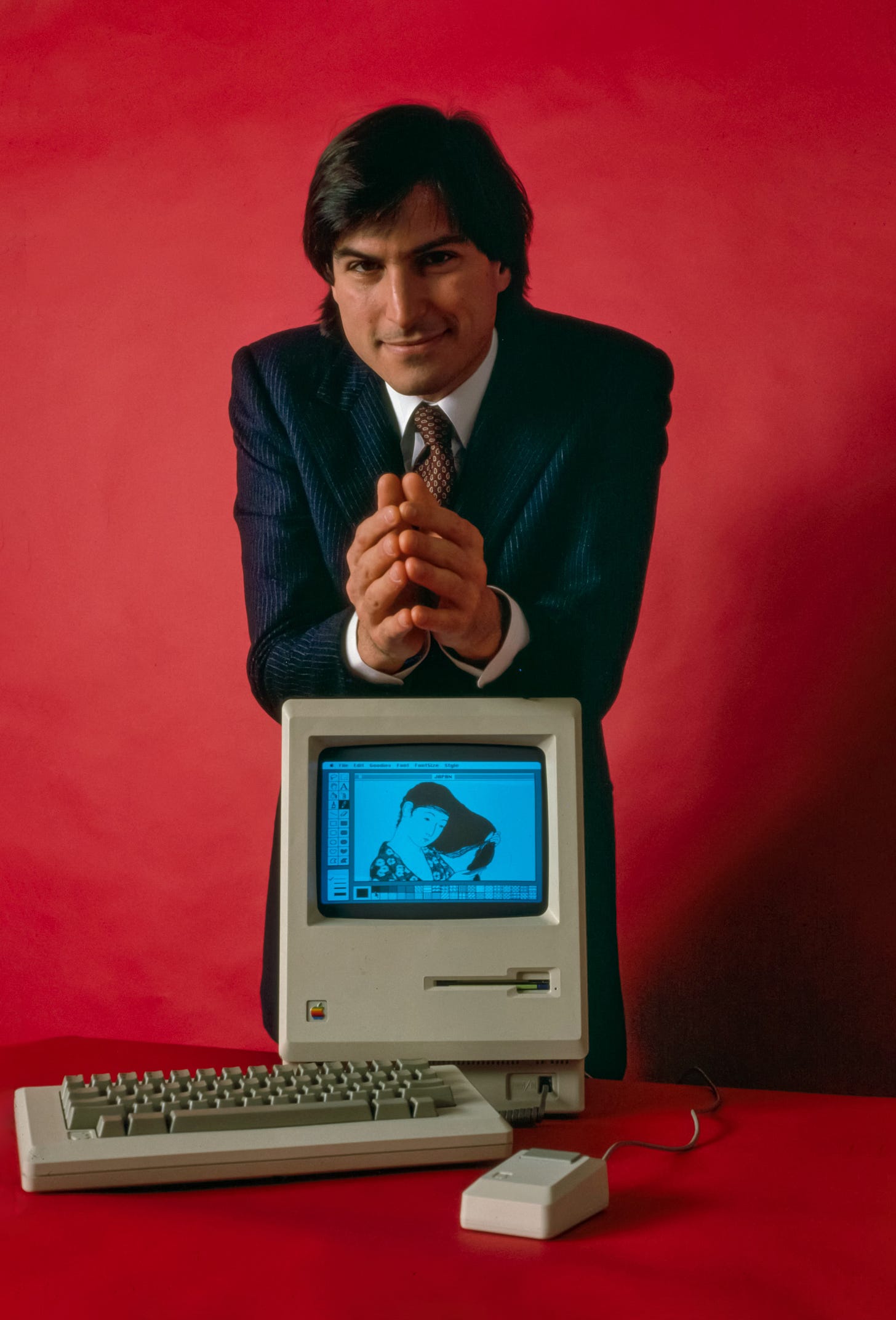

Historically, I would say, things around the early Macintosh and Steve Jobs. It was obviously a product. It was commercial. It was designed for a mass market. But at the same time, there was this sense of playfulness.

I'm trying to think of current things that feel that same way. There are a number of interesting hardware experiments, and there are certainly many things that I think are just straight up playful. So, for example, Neal Agarwal. His website is neal.fun, and he makes these amazing online toys and experiments. They're so delightful and weird and provocative that they basically force you to realize that the web can be a lot more than just Google Docs.

In terms of the blend. They exist somewhere out in the universe, these people. I think you're getting at something that's very, very challenging, which is the tension in technology between inventiveness and capitalism.

So going back to the 1960s, you have the counterculture, you have what Fred Turner dubbed the New Communalists, who come out and build out Silicon Valley. The original Macintosh was very much a part of this. And these tools were really tools designed for expressiveness. The idea was to give humans the ability to do things that they couldn't do before.

Now in Silicon Valley, you have this massive tension between, you know, I want to control what you're doing for profit. If you're on my social media network, I want you to see certain posts because that will drive ad rates up. Therefore, I'm trying to limit expressiveness to things that are more profitable. Google Docs and the like are not infinitely expressive. They don't have plug-in infrastructures. There's no way to upgrade them, change them.

Danny Crichton:

I guess the question is: In that world, to what degree are there new sustainable funding mechanisms? How do we start to think about creating those spaces so that people can do those fun widgets, people can experiment on the edge? Does it require new types of funding? Is there a place for maybe traditional institutions to come into this?

Samuel Arbesman:

I'm not sure it's an either/or — like, it's either a nonprofit or it's a venture backed company that's going to scale. I think there are ways of threading the needle. Potentially through lowering costs of overhead, lowering cloud costs, along with the ability to use AI to develop some of these things. I think we are going to see more and more companies or software products that can be sustainable and successful without necessarily having to take on huge amounts of funding.

That's kind of related to this other idea called end-user programming, which is where the user themselves is able to program and modify the software that they have. And so you're saying like, Google Docs doesn't have all the features I want. Hopefully in that case, you can just build a small feature for yourself.

But maybe that is some weird utopian vision of software for the future.

Laurence Pevsner:

Do you think it would be useful to start teaching people, even in undergrad, that code is not just a hard-for nerds-science thing? That it can be a part of the arts?

Samuel Arbesman:

I think that is completely the right way to think about it. Think about math. There's the utilitarian thing, but there's also this whole domain of recreational mathematics. I remember reading a collection of columns, I think it was from Scientific American by Martin Gardner. I think his column was titled "Mathematical Games." And it was just this playful, weird stuff. I was blown away by it.

I feel like the same kind of thing can be true with code. I'm not the only person to advocate for this kind of thing. Lots of people have done this. There's a whole domain of creative coding, where it's building software that is almost a work of art.

Danny Crichton:

Let's do your third part of the book because you have an entire section on reality. You're sort of going from programming languages, spreadsheets, all these different tools that allow us to express thought into code and into the computer to the ability to simulate different things in reality. What was your goal for this part?

Samuel Arbesman:

Well, there are two aspects. One is to show that code and computing can touch upon huge swaths of the real world. So you can, in the process of thinking about code, gain insight into various aspects of biology, or you can simulate the world with higher and higher fidelity.

But the other really important aspect is the idea of humility. I think this is related to a lot of the Riskgaming ideas you both develop: The world is really complex and we need to internalize that idea. We can make more and more sophisticated simulations, but as humans, we are really bad at thinking about nonlinear systems with huge numbers of interacting parts. Being able to understand the ways in which actions have unexpected consequences, the systems bite back, and things like that — that is really important.

I try to articulate some of those ideas, but I also discuss it in terms of the endeavor of debugging. So when you are building software you also spend an inordinate amount of time making sure it works and getting rid of glitches and errors and all the unexpected behaviors. And I feel like that is just one long exercise in teaching the programmer humility. We think we understand the world, but there's always a gap between how we think the system operates and how it actually does what it does.

Related to that is the fact that when we think about computing, we often forget that software is still in some sense deeply physical. We think of it as this evanescent stuff. And it is, sort of. But it's also built on actual physical machinery.

Laurence Pevsner:

Arthur Clarke has that very, very famous quote that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. He also has that inverse quote, you know, magic is just science we don't understand yet.

In this book, you're kind of making the opposite argument that, even as you start to understand all of this more, the magic is still there. I'm wondering why you think deeper understanding actually leads to a better appreciation of the code?

Samuel Arbesman:

One of the things I think about is my grandfather. He lived to the age of 99 and he was a lifelong reader of science fiction. I think he read Dune when it was serialized in a magazine. And I remember when the iPhone first came out, I went with him and my father to the Apple store. He looks at it and he says, "This is it! This is the object I've been reading about for all these years.” And I feel like we've forgotten that moment of like, my God, this is like an object dropped from the future or an object from science fiction and gone right to complaining about camera resolution and battery life.

In our kind of current moment, it's very easy to be jaded or cynical, and that's kind of a mark of sophistication. Maybe I'm just temperamentally unable to do that. I think this stuff is so amazing, and it bears getting excited by it.

Danny Crichton:

What Sam is saying is that, on his The Orthogonal Bet podcast, his enthusiasm is an authentic mark of sophistication. Over here on Riskgaming, I look sophisticated with my cynicism and negativity. But I'm not.

At any rate, I think we will all be richer humans by reading The Magic of Code: How Digital Language Created and Connects Our World—and Shapes Our Future. Sam, our scientist-in-residence here at Lux Capital, thank you so much for joining us.