If you live in a city in North America or Europe, you almost certainly have had the experience of watching a construction site slowly morph into a building over the course of many years. You might ask, “why’s it taking so long” as you traipse through a dirty sidewalk shed, frustrations mounting. You are not wrong, since construction has flatlined on efficiency even as other industries find ever novel ways to maximize productivity.

The search for efficiency and its disappearance is at the heart of Brian Potter’s new book, The Origins of Efficiency. Through the book by Stripe Press and his popular Substack newsletter Construction Physics, Brian has tried to explain to an angry if curious public how construction actually works in the real world and why it’s an industry both ripe for innovation yet also mired in antiquated techniques.

We talk about the challenges of construction, why the variability of site selection is a huge problem, the lack of economies of scale in construction, and the regulatory burdens plus NIMBYs that make building so difficult. Then we talk about why Brian doesn’t think aesthetic uniformity has improved efficiency over time before talking about his writing process and how he does such in-depth research.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. For the full conversation, please visit our podcast.

Danny Crichton:

I feel like you’ve become the singular ambassador between the world of bits and the world of atoms. Why are people so interested in this subject and what got you into it?

Brian Potter:

My background is in the physical world: in the construction industry. I spent the first 15 years or so of my career as a structural engineer designing buildings and parking garages and water treatment plants and those sorts of things. The industry always seemed extremely backward and inefficient to me. Buildings are so slow to go up, and the way they go up is not that different from how we built them a hundred years ago.

And then in 2018, I had a chance to join this construction startup called Katerra. This was back when SoftBank was writing checks to anybody who walked in the door. They had given Katerra several billion dollars in venture capital to revolutionize the construction industry — to take what seemed like a very backward industry and move it into the 21st century, to build things in factories … the same way everything else made efficiently is built.

The same way Henry Ford came along and established a new, more efficient way of building cars … I thought something similar would happen with construction.

I was very excited to join this company because I thought their mission was spot on. To the extent I had a thesis, it was that construction is locked into some sort of bad equilibrium where the incentives force people to do things in suboptimal ways. And to disrupt it, you need a sufficiently big jolt to the industry. I thought, “Okay, well these guys have $2 billion, that’s enough for a pretty big jolt. They’ll be able to come through and establish this new, more efficient way of building buildings.”

The same way Henry Ford came along and established a new, more efficient way of building cars … I thought something similar would happen with construction. But it didn’t work out that way at all. They burned through their funding, and in a few years, they had to start laying people off. I left after five or six rounds of layoffs. After I left, they ended up going bankrupt. In the aftermath of that, I wanted to understand what had gone so wrong.

The thesis they were operating under was that you just need to move these operations into factories — that’s what you need to do to make processes more efficient and be able to produce things more inexpensively. That idea wasn’t really enough, though. Lots of people had tried that exact same thing, and it had never really worked. There’s a huge graveyard of companies that tried similar ideas. And I wanted to understand why that was and what about the construction industry was so hard to change.

I came to the conclusion that if we keep doing this thing and it keeps not working, we clearly don’t understand something about what it takes to make a given process more efficient. And so I started writing this newsletter, “Construction Physics,” about the construction industry. And this idea that we need to understand what it takes to make a process generally more efficient was the genesis of the book, The Origins of Efficiency.

Danny Crichton:

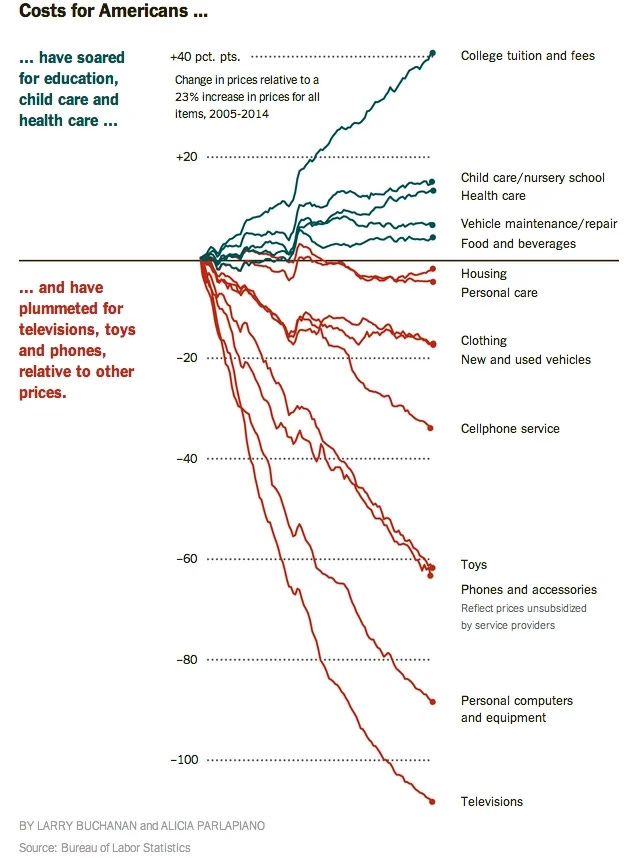

I’m sure a lot of our listeners have seen the viral chart graphing real cost differences between the early 2000s and today. If you look at, say, chips, those have massively improved in performance while costs have gone down, following Moore’s law. And then you have categories like construction, hospitals, education, and some other human services that have actually gone up in cost over time; they’re far more expensive today than ever before.

I guess the question is why the origins of efficiency and not the origins of inefficiency?

Brian Potter:

So for building stuff — for construction specifically — the thesis I’m operating under is that there are specific things you can do to make some process more efficient, and if you can do those things, great. Whatever you’re making, you can find ways to make it cheaper over time. If you can’t do those things, then you’re kind of screwed. It’s very, very hard to make whatever it is that you’re doing more efficient if those paths are blocked.

With construction, it turns out that all these strategies available to make some process more efficient are very, very hard to do in construction. And so you have these paths to efficiency that are blocked or extremely narrowed. And at the same time — and construction is not unique — we’ve made it increasingly difficult to do the processes that we have. There’s increasing regulation and increasing administrative and bureaucratic overhead in general. Things take more steps than in the 50s and the 60s, when we could go a little bit more by the seat of our pants.

Danny Crichton:

One of the theories I’ve always heard is that general contractors are sort of managing the construction project at a high level, bringing in subcontractors. You bring in electricians, you bring in duct work, you bring in folks who are doing plumbing, whatever the case may be. And one of the challenges is that there’s a lot of thrashing, and building sites are not full all the time. Just on my block in New York City alone, there are three building sites. There hasn’t been work done on any of them in three months. They’re just sitting there. One is a three-story townhouse. I think we’re in year four of construction for a building that is roughly 2,000 square feet.

Are there organizational behavior changes on the construction side, whether it’s the site, the general contractors, subcontractors that make it hard to be efficient?

Brian Potter:

Yeah, it’s interesting. You talk about the contractor breakdown, where each task is done by a separate subcontractor. They’re responsible for one little thing. Some mechanical engineer or mechanical company will come and install the HVAC system or whatever, and they’re a separate company than the guys doing the plumbing and the guys doing the framing.

But that’s not necessarily that different from how other industries operate, right? Ford doesn’t manufacture every single part in their cars, right? They have hundreds of suppliers, they have tier-one suppliers and those tier-one suppliers have their own suppliers and so on down the line. But when you’re doing very repetitive operations, it’s much easier to coordinate these steps, so everything moves a lot more smoothly from one thing to the other.

It doesn’t work like that in construction, for a variety of reasons. Part of it is regulatory, and part of it is that these are all separate businesses. But buildings themselves are also unique. You’re building something different every time. And so it’s hard to get your process dialed in, and you’re finding surprises, or someone puts a pipe in the wrong place because this is their first time building the building. And so there are all these things that conspire to prevent you from having a really swift and smooth process.

People often theorize that you can’t have mass-produced housing because people demand too much uniqueness in their homes. I don’t really think that is true.

Danny Crichton:

When we look at housing in particular, there is this spectrum from a completely prefabbed house — like a trailer or double wide or something like this — to, when you get into cities, almost every apartment going up is unique. Every building has its own design.

How much do you think about the aesthetic concerns? I mean, there’s NIMBYism, and that shows up in historical preservation, but why can’t we be a little more process oriented? Is it purely aesthetics or is there something deeper?

Brian Potter:

Yeah, that’s a good question. I think the aesthetic aspect is a little bit overrated. People often theorize that you can’t have mass-produced housing because people demand too much uniqueness in their homes. The house is a reflection of them, and they want to have a house that works for their specific needs.

I don’t really think that is true. If you look at the housing that actually gets delivered, it is quite repetitive. Large-scale home builders have a library of a relatively small number of houses, and they’ll plunk those houses down in developments all over the country.

People are willing to accept a fair amount of uniformity in their housing and in their buildings, especially if that uniformity is associated with a significant cost decrease.

I live in a housing development built five years ago by a small local developer. It has four or five different floor plans, and those floor plans are just copied over 80 different houses. I live in a long line of houses, where every single one is the exact same floor plan, just sometimes mirrored, sometimes with slightly different finishes or whatever. It did not stop anybody from buying up those houses. It has not had any effect on the valuation of those houses.

In general, I think people are willing to accept a fair amount of uniformity in their housing and in their buildings, especially if that uniformity is associated with a significant cost decrease. I think people would be very on board with that.

The lack of uniformity has more to do with other factors — like different sites are different. They’re different shapes and utilities come in from different places and the ground has different properties and different parts of the country have different wind forces and different earthquake forces and different temperatures or whatever.

Housing is not like semiconductors, where you can make a billion in a single factory in Taiwan and then ship them all over the world. You’re building a relatively small number of units, and you can transport those only a relatively short distance. If you can’t get huge economies of scale, the returns from having a completely uniform product are not nearly as high.

Back when I was in the construction industry, I would sometimes work on projects where we’d have a basic design for a building, but we’d need to adapt it to the specific site. You do save a decent amount of time because you’re not redoing the whole thing from scratch, but you couldn’t cut and paste it from one place to the other.

Another big part of it is the market is not quite big enough to accommodate a really huge amount of uniformity. Part of that is due to transportation costs — you can’t move stuff a super long distance. Housing is not like semiconductors, where you can make a billion of them in a single factory in Taiwan and then ship those all over the world. You’re building a relatively small number of units, and you can transport those only a relatively short distance. If you can’t get huge economies of scale, the returns from having a completely uniform product are not nearly as high.

Danny Crichton:

Are there examples in construction or manufacturing where there has been a dramatic revolution that really improved efficiency? And then on the flip side, are you cynical about certain parts of the industry where it seems like it will be impossible to see any change going on in the next 10, 20 years?

Brian Potter:

This is not an especially interesting answer, but the stuff where there’s a ton of regulation or other constraints makes it hard to have the flexibility to do new things or try something and fail, and use that as feedback.

So nuclear power is an example. Where it’s so regulated, it’s difficult to go in and try something and see how it works, and if you fail, learn from that failure. You’re prevented from doing that basic thing in nuclear power construction, especially in the United States. Other countries have managed to do it better. I’m not an expert on South Korean nuclear power regulation or Chinese regulation, so I couldn’t really speak to that. But in the United States especially, you’re so constrained from experimenting that it makes it really difficult to see where you can improve.

Danny Crichton:

When you think about the rise of AI over the last two years, the United States is bringing on tens of gigawatts of additional power in order to power all this. It seems like we have a construction boom. As some estimates say, half of last year’s GDP growth was driven by AI investments. Are there lessons from there to port to the rest of manufacturing and construction?

Brian Potter:

The amount of data center spending is now as much as — or more than — commercial office spending. So we’re building more data centers than we are office buildings, on some level of measurement.

One thing you’re seeing with this data center build-out is that data centers have been a relatively popular thing for jurisdictions to build. Local governments or whatever wanted these centers because they came in and paid a decent amount of property tax revenue, but didn’t place many demands on local services, since there were not that many people in these things. They needed water and power, but they’re not using extra police force capacity. You’re not stressing the school capacity, you’re not stressing road infrastructure or stuff like that.

So it’s like, “Oh, great, these guys will come in and build this big thing and pay me a bunch of property tax and it won’t incur a bunch of extra local government costs.” But now you’re starting to see a lot of local opposition. NIMBYism, which historically wasn’t really a factor in data center construction, now is much stronger. You’re really starting to see local opposition because these things are so big and are creating such big demands for electric power.

Danny Crichton:

The epilogue in your book looks at the future of construction manufacturing, taking lessons from the origins of efficiency to the rest of the 21st century. If you’re a policymaker, what are the top two?

Brian Potter:

One is this: It is very hard to predict what is going to be important and what is not going to be important. And so you want to give yourself enough flexibility to take a variety of approaches. This is a high-level idea that encompasses a lot of different things.

For any given technology or process, there’s often a large variety of ways to implement it, and it’s not necessarily obvious what the best one is, so it is good to have flexibility.

Kind of like I talked about earlier: It’s nice if you can experiment and learn from those experiments. It’s nice to be able to sort of solve problems in a bunch of different ways. For any given technology or process, there’s often a large variety of ways to implement it, and it’s not necessarily obvious what the best one is, so it is good to have flexibility.

The second one is that being able to achieve economies of scale is quite important. We see this in shipbuilding. There are lots of ideas for revitalizing the shipbuilding industry, which is good and admirable. But people don’t often come up with an obvious path to make it competitive in a world market where there’s already these other companies operating at huge scales and have poured huge amounts of money into these shipbuilding facilities. Are we really going to be willing to bite that bullet and make similarly huge investments?