The future of defense manufacturing with Anduril CEO Brian Schimpf

Making U.S. tech fast, cheap, and cool

Lux portfolio company Anduril has become one of the most-watched companies in Silicon Valley, and for good reason. Its vertiginous rise from small hardware laboratory to next-generation defense prime has entranced engineers and investors alike, and it has also garnered an increasingly long record of success in Washington DC.

Yet for co-founder and CEO Brian Schimpf, the real magic of Anduril has been its ability to scale design, manufacturing and its culture from a dozen early employees to more than 4,000 today. Brian’s maniacal focus has been on ensuring that Anduril never becomes a legacy defense prime ploddingly delivering half-baked products to the disappointed faces of warfighters. Instead, he and his team have tenaciously strategized on business models, contract negotiations, tuck-in M&A, engineering culture and manufacturing centralization and decentralization to ensure that Anduril always offers the highest-quality and most cost-effective products in the marketplace.

In this interview, originally recorded in November 2024, Brian talks with Lux’s own Josh Wolfe about his own founding journey at Anduril, the company’s burgeoning portfolio of products, and how it’s rebuilding the arsenal of democracy in the years ahead.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. For more of the conversation, subscribe to the Riskgaming podcast.

Josh Wolfe:

I want to talk about two trajectories. Trajectory one is the trajectory of Anduril, of the company. And trajectory two is the trajectory of the projectiles I believe are defining modern warfare: missiles and missile defense.

But let's start with the trajectory of the company.

Brian Schimpf:

We had been talking for years about how there needed to be a new defense company, a new defense prime. The realities of the world, all the macro forces, all the inventions in Silicon Valley, the way you build modern software, the need for lower costs, more autonomous systems — these were all major shifts that were just not being seen in the defense space.

We believed there was this opportunity to do something big, something different. And that was a pretty wild idea at the time. In 2017, I was at Palantir, and the conventional wisdom was to focus on a single product. That's what you do as a company.

The idea that we would have a broad portfolio of products was a weird concept for a lot of VCs at the time. It didn't make a lot of sense. But for us, it seemed kind of obvious that you needed something new in defense.

Fast-forward seven years later, and the pace that we've been able to move surprised even us. For SpaceX or Palantir to get to different revenue mile markers, it took five or ten years. We were about two years in when we had our first quarter-billion-dollar program moving very, very fast. Today we're about 4,000 people. A year ago, we weren't making autonomous fighter jets. This year we are.

We've been able to accomplish a huge amount of stuff. A lot of it is just due to the macro environment. Tech has changed, the world is in the most geopolitically unstable place it has been in our lifetimes, and the need and the urgency around solving some of these problems — I just haven't seen before in my lifetime.

Josh Wolfe:

In 2019, I remember being at the Reagan National Defense Forum with you, and Palmer Luckey and Trae Stephens and a handful of others were on a panel. Palmer was in his classic get up of Hawaiian shirt and cargo pants and his flip-flops. And I remember the feeling, it was almost like that Gandhi quote. First they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.

How did you win? Was it the fact that the technology was superior?

Brian Schimpf:

I really think this started to shift over the last 12-18 months. And there were a couple of different things. Probably the biggest single mover was that we were in a competition against Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Northrop to build this autonomous fighter jet program, and we won. It's one of the Air Force's top priorities. They saw and understood that we could do things cheaper and on a faster schedule. That we were showing up with ideas of how this could be different, and they took the bet. That has catalyzed a major shift.

We've also seen it working on counter-drone systems. We invested our own capital to build a surface-to-air counter-drone missile. Nobody else would've done that.

Nobody has a weapons program just on the hope that the U.S. government's going to buy it on the other side. But we knew it was a need. We knew it was a problem that needed to be solved. We listened to the department on what its priorities were, and we just kind of ran to the sound of gunfire.

Josh Wolfe:

Well, let's talk about that. People complain that the primes are sclerotic and bureaucratic and slow moving. And mostly it has accrued to their advantage to be like that. But along comes Anduril and all of a sudden the speed with which you are ideating, the speed with which you are producing and delivering, it's a game changer. And it hearkens back to the World War II effort.

How was it when you were thinking about going from an initial set of products, like you were assembling sentry towers for Customs and Border Patrol, into autonomous copilots of fighter jets?

Brian Schimpf:

We have a software core we call Lattice. And the idea is to think of broad platforms that could be useful across a huge array of things. The tech world has realized how expensive, how difficult platforms are to build, so if you actually have a general one, the number of problems you can solve, the number of areas you can tap into, is massive.

This idea of building Lattice was cross-cutting with everything we do. Beyond that, all the systems we have, have a huge number of sensors on them. They have to make sense of the world, they have to process it. We use all sorts of different AI techniques to do that.

And then the other end of it is that we're building robotic systems. They've got to interact with the real world. So how do we actually go out and plan how an aircraft flies, how it manages hundreds of decisions. Am I going to be seen by the adversary? Where do I point my sensors? I've got to get the best advantage to take this shot. All those things have to be taken into account, which is a very hard thing for a human pilot to do. But codifying that into software becomes really, really key.

If there isn't an aspect of cheaper, higher quantity, smarter, more autonomous, it's probably not interesting for us.

We're not really doing anything with manned platforms. We're not going to make an F-35. We're not going to make a tank with people in it. It's not what we're going to do. And that's enabled us to basically think about where we can make things cheaper. Where can we tap into a different supply base? How can we re-conceptualize the design to make it easier to manufacture and really make it software enabled from day one?

These are questions that permeate every single thing we're doing. The reality in defense, though, is you aren't going to get a single product winner. And honestly, you're not moving the needle on national security by having one product. We want to have as big an impact as we can on the military strength of the United States. That's going to require getting into sensors, that's going to require getting into weapons, that going to require getting into aircraft and subsea platforms.

And if there isn't an aspect of cheaper, higher quantity, smarter, more autonomous, it's probably not interesting for us.

Josh Wolfe:

Let's talk about speed. Why does it take the big primes so long to iterate?

Brian Schimpf:

The primes are a product of the government incentive structure they live in. They're living in a world where everything is a government process. They get requirements, and they're bidding to spec. They go through a very sequential design prototype test, then get to the mission test. So when you look at that whole cycle, it’s like 10 to 15 years. A fast weapons program for the U.S. military is 12 years. That is considered record speed.

This is how to sabotage an organization: Everything needs to be reviewed by committee.

Josh Wolfe:

I remember when Tony Thomas, one of our venture partners who used to run SOCOM, sent me out to the Pacific. I came back and did an out-briefing in the Pentagon. I said, "If I was an adversary, the number one thing that I would do is basically take that character from Office Space with the red stapler, and just put him in charge of everything because I would just want to slow the system down and put as much friction as possible."

Brian Schimpf:

Yeah. This is how to sabotage an organization: Everything needs to be reviewed by committee.

But we have incentive to get products out fast. We're investing off–balance sheet. We don't make any money until it actually works. And we've embraced a lot of the Silicon Valley DNA, which is to empower very smart engineers to go out and crush problems. We're not so risk averse that we have to double check everyone's work. We want to set up processes to ensure nothing goes wrong, but a lot of the primes feel like they have more to lose than to gain by moving fast.

Josh Wolfe:

It is a testament to your leadership style as CEO that you now have 4,000 employees. We've got 40 people here at Lux, and at times that feels to me unmanageable. Talk about how you manage all those people and how you keep up the speed, the innovation, avoid the bureaucracy.

Brian Schimpf:

We have a bit of a structural advantage in that we have so many products we're working on in so many diverse business areas that each team can be a small organization. And it can actually still be very agile, very nimble. Every time there's a problem, it isn't an opportunity for more processes for second-guessing. It is a learning opportunity for those leaders to get better and fix their organization. And so we're always doubling down on autonomy, on local control.

Josh Wolfe:

Let’s shift now from the trajectory of the company to the trajectory of missiles, which I believe are one of the key defining technologies for modern militaries.

You're seeing it in Russia, Ukraine, you're seeing it in Iran, in Israel, Gaza, Lebanon, Hezbollah, the Houthis. So let's talk about missile defense and the systems you're developing.

Brian Schimpf:

I agree that this is one of the key technology shifts. When you look back to the early 2000s, it was a small number of states that had the technology to do long-range strikes. And so it was viewed as a fairly high-end technology. But the Iranians supplied it to everyone. It's relatively cheap and easy to build low-cost drones. These can go hundreds of miles and strike things at huge ranges.

That’s massively shifted where you can be safe, what enemies can put at risk. It's pushed everyone back substantially. The United States has had air superiority without any threat of long-range strikes for so long that we've really atrophied on missile defense capabilities.

We've invested into things that were high-end like the Patriot missile, which is good for taking out long-range ballistic missiles — the state-level threats. But it has less ability to deal with these sorts of low-grade, high-volume threats.

In Ukraine, the data on this is just wild. Low-cost suicide boats have taken out a third of the Black Sea fleet and rendered the other two thirds of it effectively useless. It has to stay so far back that it is not even relevant to the fight at this point. Russia has deployed something like 8,000 Iranian Shahed drones against Ukraine over about a two-year period. And that's not counting their other conventional missiles as well. So the scale is absolutely massive. They've taken out tanks, tanks are irrelevant.

We've got two things we're investing in on that front. One is counter-drone tech. This is a hard problem on a couple of different stages. You’ve got to detect and track them. That's hard. There are some flying 50 feet off the ground. Man, that is a hard thing to find.

Josh Wolfe:

At speeds of?

Brian Schimpf:

At speeds of hundreds of miles an hour, so you don't have a lot of time to react. All of this is a very, very hard detection tracking problem.

Then you've got to be able to affect them. For example, I want to jam them, I want to confuse them with electronic warfare, or I want to strike them. We've invested in all of the above. Lattice really helps in that detection/tracking fusion. We've invested in a variety of sensors there. And then we've done electronic warfare systems where we're doing novel jamming technologies using RF machine learning to identify signals and be able to react very, very quickly.

We've done a lot on the kinetic side as well. Again, this was funded off our balance sheet. We just saw where the threat was going. We built this technology we called Roadrunner. It's basically a vertical takeoff and landing. It looks like a mini fighter jet. You can kind of orbit, and then once you decide you want to engage a threat, you can blow it up. Or if you don't, you come back and land. We have that deployed throughout the Middle East. We're getting it deployed with all the services right now, and it's scaling quite quickly.

Josh Wolfe:

When you look at strategy — whether against Iran, Israel or China — the idea of attritable systems frequently comes up. These are large-scale, relatively cheap technologies that saturate a particular adversary's ability to defend itself. I think it's something like for every 14 missiles an enemy fires, you can immediately fire 28 back. But the enemy’s 15th shot can effectively kill you. That's a very complicated calculus. What are some of the non-obvious approaches where technology might be used here?

Brian Schimpf:

There have been three big technology shifts that have made most of the legacy approaches very, very hard to execute.

The first is the proliferation of long-range weapons, and the second is absolutely ubiquitous sensing. So again, there's no sanctuary. You can be found anywhere. Even things like stealth are becoming increasingly challenged with the types of technologies the Chinese in particular are investing in. The third is the ability to ubiquitously network all this information together. You can now get a comprehensive picture of the battle space across many, many systems simultaneously.

So if you combine all these things, you're down to this world where you can't hide and it is very hard to maneuver. That leads to the conclusion that, first, I’ve got to have that strategy too. I've got to have the mass and the ability to engage. But it pushes me away from having few high-value targets like big ships. And it pushes me away from how we've viewed defense in the past, which is, okay, I'll have these high-value targets but then I can use them to shoot down missiles incoming. Well, if you're a destroyer in the South China Sea and you're expending your entire magazine just to defend yourself, why are you there? What's the point?

The belief we've had on this is that is all these things drive you to more mass, more scale, make it so confusing, so overwhelming for your adversary that they can't economically defend themselves anymore.

Josh Wolfe:

The means for the mass you're talking about is manufacturing. So let's talk about manufacturing because it's what helped the allies win in World War I and II. China seems to have an ability, whether it's shipbuilding or missile or munitions that is far exceeding ours. What are you guys doing about that?

The reality is that the United States has focused too much on luxury good items in defense. These are artisanal, handmade products.

Brian Schimpf:

Let's take stock of where the United States is today. You look back to the Cold War, and nearly every company in America was participating in the defense industrial space. They were supplying components or they were building something in support of the U.S. apparatus. Today there are very few companies doing so, and the companies supplying for defense generally aren't supplying competitively into the commercial space. It's quite separate. Our contention is that it doesn't have to be that way.

The reality is that we have designed these luxury good items in defense. These are artisanal, handmade products. We never update the process by which we make, we're not taking in new suppliers. And meanwhile, in the automotive industry, companies like Tesla have just completely upended it. So when we look at this, first and foremost is the design phase. If we're not actually designing things for manufacturing at day one, you just can't do it.

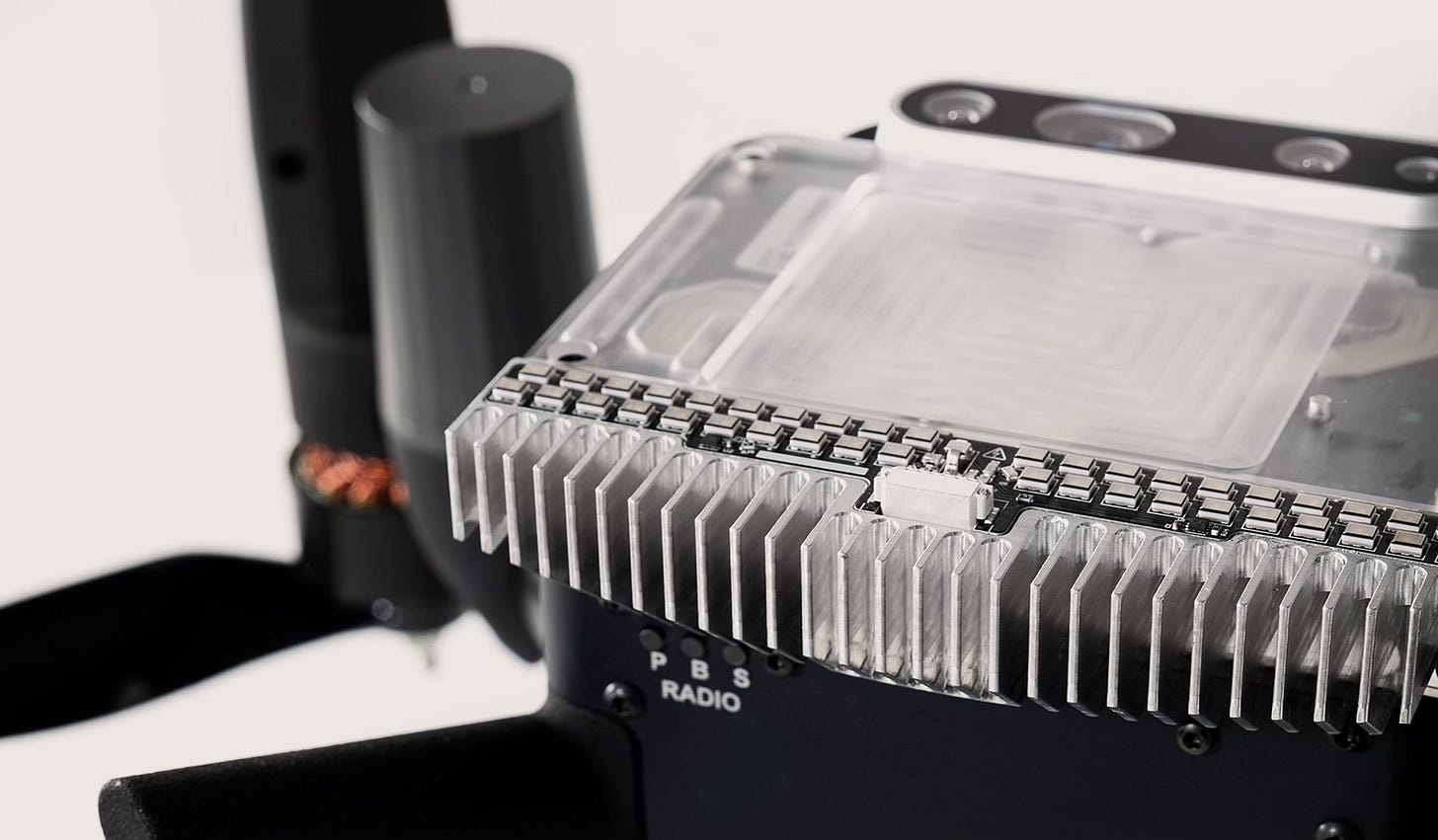

We're working on this one missile, we call it Barracuda. It's something like 95% fewer tools to actually assemble this thing. We literally make the exterior fuselage in the same way people make acrylic bathtubs.

So okay, great, we've designed it well. Now we need to tap into a commercial supply base. These are the companies that, in time of war, are going to be able to scale with you. You're using maybe 5% of their capacity normally. If we're in a war, we can ramp that up 20X. There's a huge breadth of suppliers that can actually do this.

The other piece we've focused on is building out a large factory complex we call Arsenal. The idea here is that what we're going to be building in ten years will be wildly different from what we were building today. The volume's going to change. The mix is going to change. So we can't operate with big fixed infrastructure. Everything has to be very adaptive so that I can constantly evolve the mix of products. And those products need to be able to refresh, change, modify every month.

Josh Wolfe:

When people ask what's going to be the Tesla or the Apple of defense, everybody says Anduril. The products are stunningly beautiful. However, these are things that are going to explode and disappear. And so why the attention to putting out beautiful things?

Brian Schimpf:

We think about three aspects.

One, paying attention to design forces the engineers to take in everything. There's just an aspect of giving a shit, caring. You're trying to make this a great product that you're proud of. That really matters.

Two, the brand side really does matter. We want to have something that people look at, that they affiliate with the types of products we would build, that they're excited about.

Defense isn't a sleepy industry. It's something that is important, that matters, that you can be proud of.

That applies to our employees, but it also implies to the soldiers and operators using our tech every day. They should have something they're excited about. They should feel like they have the best technology. Making the military cool really matters.

Three, at the end of the day, there's a theatrical aspect of projecting power. If it looks like you have the best stuff, it looks like you are powerful. And that is important for the U.S. military. This generation of drones can't look like derpy drones. They've got to look as badass as F-35s.

Josh Wolfe:

Brian, as a stakeholder in Anduril and as a stakeholder, an American, in our country, I’m extremely grateful for your leadership as CEO. Always good to be with you.

I really enjoyed this. Thanks, guys.