Poisoned in the skies, AI invents disease, and why AI won’t make you rich. Plus, looking back on Tom Wolfe.

Quick Plug: William Knudsen Industrial Policy Fellowship

Charles Yang and our friends at the Center for Industrial Strategy have launched a new fellowship aimed at training “the next generation of industrialists navigate the policymaking ecosystem in Washington, D.C.” It’s a subject that is becoming ever more salient and complex by the day, and like-minded people need more opportunities to connect and discuss how to connect the atoms of manufacturing into the letters of our country’s laws. I’ve endorsed the program, as have previous Riskgaming podcast guests Jack Shanahan and Kelvin Yu.

Deadline is next Friday, September 26 and I urge you to apply.

From Lux Capital

This week, we launched our latest Riskgaming scenario, Southwest Silicon. It’s a local game with global implications, one that we have played in the United States as well as in Europe and Asia. The challenge of growing under constraints is a commonplace, and the liminal space between positive-sum growth and doom-loop collapse can be astonishingly narrow.

In short: get a group together, play the game, and let us know what you think!

From around the web

1. Cabin pressure

If you notice an “off” odor when flying: beware. According to reporting in The Wall Street Journal, “fume events” — when vaporized chemicals leak from the plane engines into the cabin air due to faulty seals — may be on the rise. Airbus’ A320 seems particularly vulnerable, but despite pressure from Congress and even affected pilots and passengers, the industry hasn’t budged on fixing the problem — or even doing much to monitor it.

That year, JetBlue pilot Andrew Myers was asked to help run tests on an aircraft that had had a run of fume events. Sitting in the cockpit, he turned the engines on and was dosed by toxic vapors that came rushing in. The maintenance crew, which hadn’t yet found the source, asked him to try again.

Coughing, he tried to leave the aircraft but collapsed at the exit and fell into the jetway.

His doctors diagnosed him with a “chemical-induced nervous system injury.” He developed chronic headaches, began stuttering, suffered severe tremors and would regularly collapse in public and be helped home by strangers.

2. Infectious intelligence

From sickening smells to sick AI? Scientist-in-residence Sam Arbesman flags Niko McCarty and his writeup of Arc Institute’s most recent breakthrough: their AI model can not only design proteins, it has now created the world’s first viable AI-generated genome, a bacteriophage modeled on a virus that infects E. coli bacteria.

Although the fine-tuned model in this paper designed viable phages with hundreds of novel mutations, the actual biology of those phages did not change — they still infect E. coli, just as ΦX174 does. In synthetic biology, though, we often care about creating new functions. The next step, it seems, will be to design some sort of “training feedback loop” with which these AI models can be coaxed to build phages with pre-specified behaviors.

I’m quite confident this will happen soon. When Frederick Sanger published the first full genome sequence of ΦX174 in 1977, using a DNA sequencing technology called di-deoxy termination, the final sequence was only 5,375 bases long. At the time, “that number represented the outer limit of gene-sequencing capability,” Siddhartha Mukherjee wrote in his 2016 book, The Gene: An Intimate History. Scaling it up to the human genome, with its 3 billion base pairs, represented “a scale shift of 574,000-fold.” And yet it happened within a quarter-century, using technologies that were not all that different from Sanger’s original method.

3. Life finds a code

Sam also liked Michael Waraksa’s latest in Quanta magazine. Michael details the research of Alexander Mordvintsev, who is working to use neural networks to automatically discover rules for cellular automata — like a reverse Game of Life — so that patterns self-assemble, rather than scientists having to manually define the rules from the start and seeing what emerges. This lets patterns regenerate after damage and adapt in surprisingly lifelike, robust ways, hinting at new forms of computation and insights into biological growth.

With this inversion, he has made it possible to do “complexity engineering,” as the physicist and cellular-automata researcher Stephen Wolfram proposed in 1986 — namely, to program the building blocks of a system so that they will self-assemble into whatever form you want. “Imagine you want to build a cathedral, but you don’t design a cathedral,” Mordvintsev said. “You design a brick. What shape should your brick be that, if you take a lot of them and shake them long enough, they build a cathedral for you?” Such a brick sounds almost magical, but biology is replete with examples of basically that.

4. Return on invention

With AI Capex surpassing the telecoms boom and beginning to rival the railroad bubble of the 19th century, it seems fair to ask which investors will profit. On that question, Lux’s Shaq Vayda recommends “AI Will Not Make You Rich” by retired venture investor Jerry Neumann, who examines whether AI innovation is more like the invention of the microprocessor, which led plenty of downstream inventors and investors to wealth, or shipping containerization, which changed the economy but made fortunes for very few.

If AI had started a new wave, there would have been an extended period of uncertainty and experimentation. There would have been a population of early adopters experimenting with their own models. When thousands or millions of tinkerers use the tech to solve problems in entirely new ways, its uses proliferate. But because they are using models owned by the big AI companies, their ability to fully experiment is limited to what’s allowed by the incumbents, who have no desire to permit an extended challenge to the status quo.

This doesn’t mean AI can’t start the next technological revolution. It might, if experimentation becomes cheap, distributed and permissionless—like Wozniak cobbling together computers in his garage, Ford building his first internal combustion engine in his kitchen, or Trevithick building his high-pressure steam engine as soon as James Watt’s patents expired. When any would-be innovator can build and train an LLM on their laptop and put it to use in any way their imagination dictates, it might be the seed of the next big set of changes—something revolutionary rather than evolutionary. But until and unless that happens, there can be no irruption.

5. Algorithmic chic

If AI does create a new elite, who would have been better to chronicle it than Tom Wolfe? Perhaps that’s part of the motivation behind Picador’s reissue of his books. On the occasion of their release, Jeannette Cooperman reappraises the author’s legacy for The Common Reader, finding that a writer such as Wolfe could not exist today — and the reasons for that may have been set in motion by the father of New Journalism himself.

Did Wolfe do such a good job capturing the present that he ruined our future? Consider the trajectory. Lippmann urged objectivity in 1920 because he saw “everywhere an increasingly angry disillusionment about the press, a growing sense of being baffled and misled.” He worried about news coming at us “helter-skelter, in inconceivable confusion,” and readers “protected by no rules of evidence.” He was afraid of a time when people “cease to respond to truths, and respond simply to opinions—what somebody asserts, not what actually is.”

Here we are.

In the century between 1920 and 2025, journalists first tried for objectivity, then broke free from convention in the 1960s and 1970s with the New Journalism, named by Wolfe and led by him, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Gay Talese, and Hunter S. Thompson. The shift would be defined by Marc Weingarten as “journalism that reads like fiction and rings with the truth of reported fact.” Its arrival rang out like a high, clear church bell, elating young feature writers. Its new freedom even colored newswriting, which began to set scenes for us, paint in vivid detail, and smuggle in the first person.

6. Soul searching

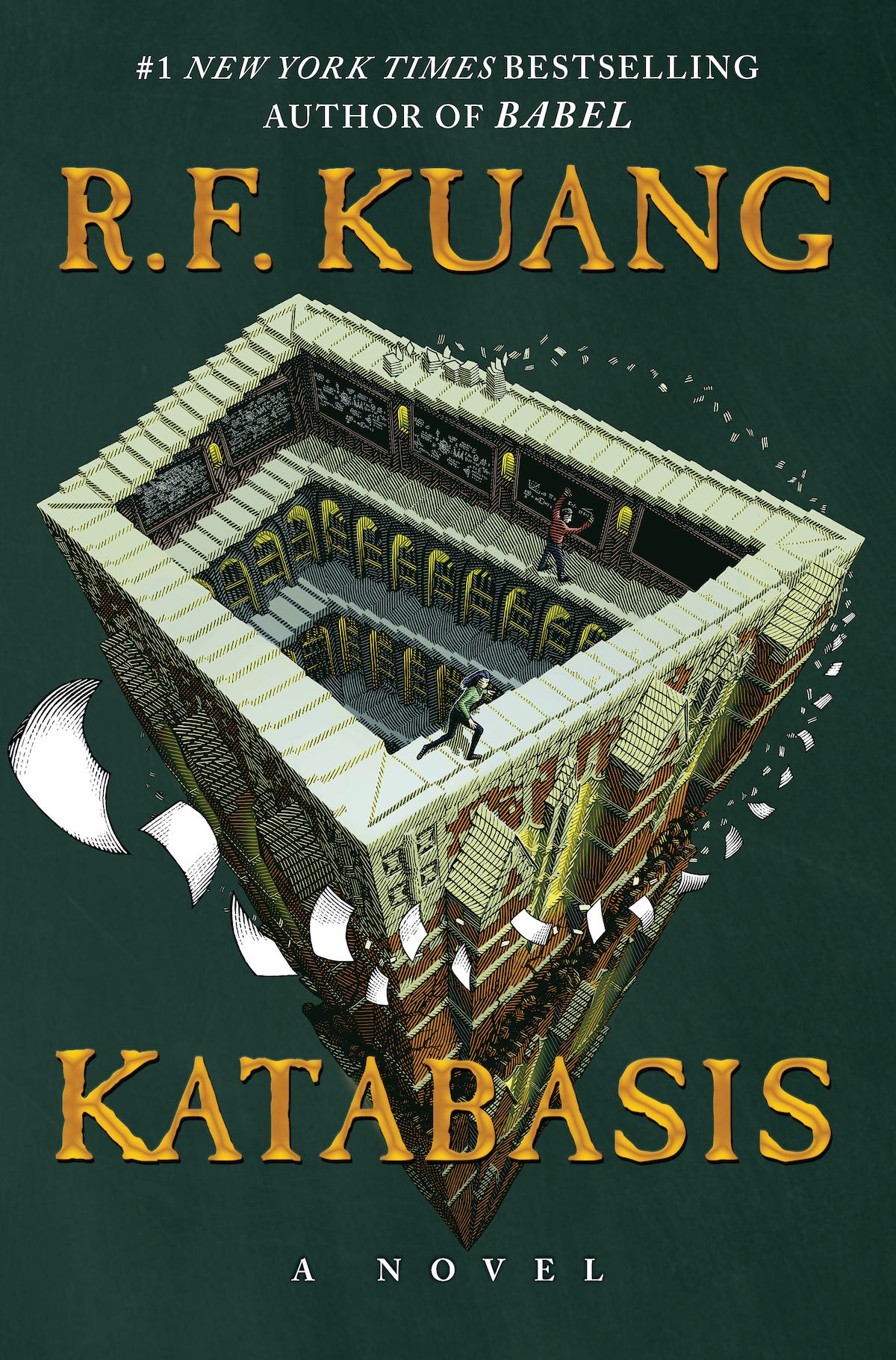

Finally, if you’ve already read Tom Wolfe and are looking for a new book, Sam recommends Katabis, by R. F. Kuang. The story follows two graduates who must venture through Hell to save their professor’s soul — and win his recommendation.